What Is the Science of Reading?

Written by Sandie Barrie Blackley, MA/CCC

Published on January 20, 2023

The science of reading has been a hot topic in education circles lately. Controversy has mostly been related to the different ways people define what is the science of reading. For example, while some have focused on the science of how humans learn to read, others have focused on the impacts of different instructional methods.

The Reading League (TRL), a national education nonprofit, has proposed this definition of the science of reading:

“The science of reading is a vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically-based research about reading and issues related to reading and writing.

This research has been conducted over the last five decades across the world, and it is derived from thousands of studies conducted in multiple languages. The science of reading has culminated in a preponderance of evidence to inform how proficient reading and writing develop; why some have difficulty; and how we can most effectively assess and teach and, therefore, improve student outcomes through prevention of and intervention for reading difficulties.” (The Reading League, 2022)

As this definition suggests, there is growing consensus about how reading and writing skills develop and what can be done to help struggling readers and writers. In this article, we’ll have a look at this reading science.

The Simple View of Reading

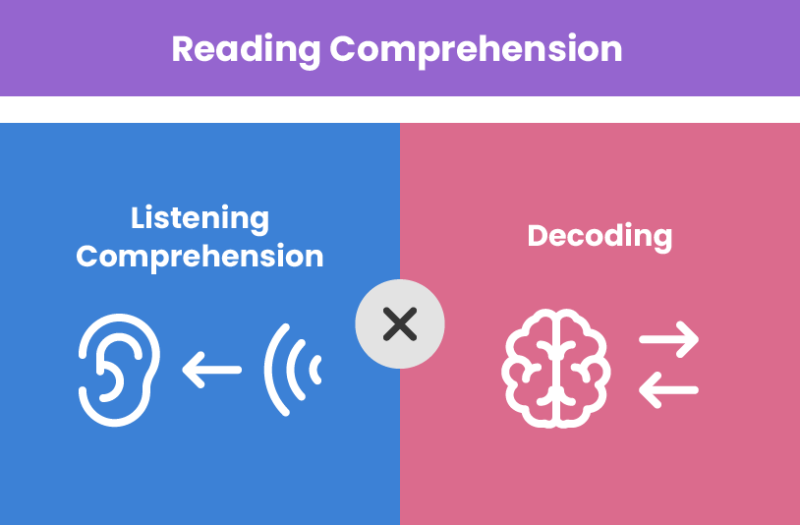

The Simple View of Reading (Tunmer & Hoover, 2019) is currently the most widely accepted model of how reading develops. It has been validated in hundreds of scientific studies. Notice the multiplication symbol (x) in the graphic below. The model holds that reading comprehension is the product of two components: listening (language) comprehension multiplied by decoding (word recognition).

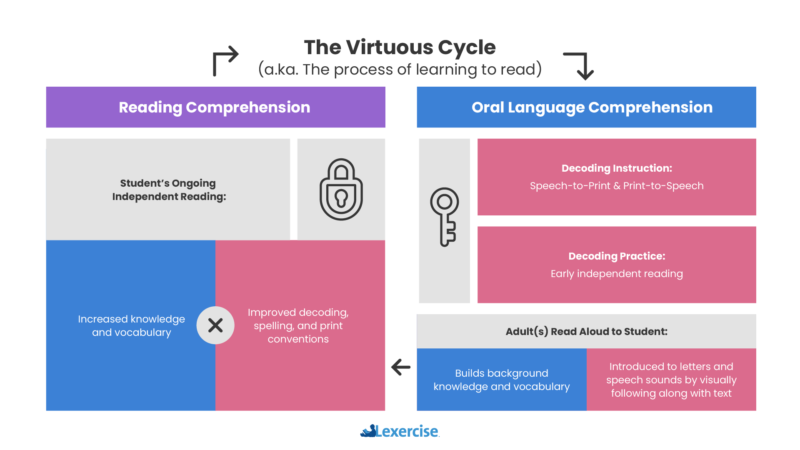

The process of learning to read has been described as a virtuous cycle, with reading comprehension as the goal. The series of graphics below illustrate how these two components multiply in an expanding and increasing cycle.

Defining the Virtuous Cycle

The virtuous cycle begins with the uniquely human feat of oral language—communication through listening and speaking. The blue blocks in the graphics represent spoken language or listening comprehension.

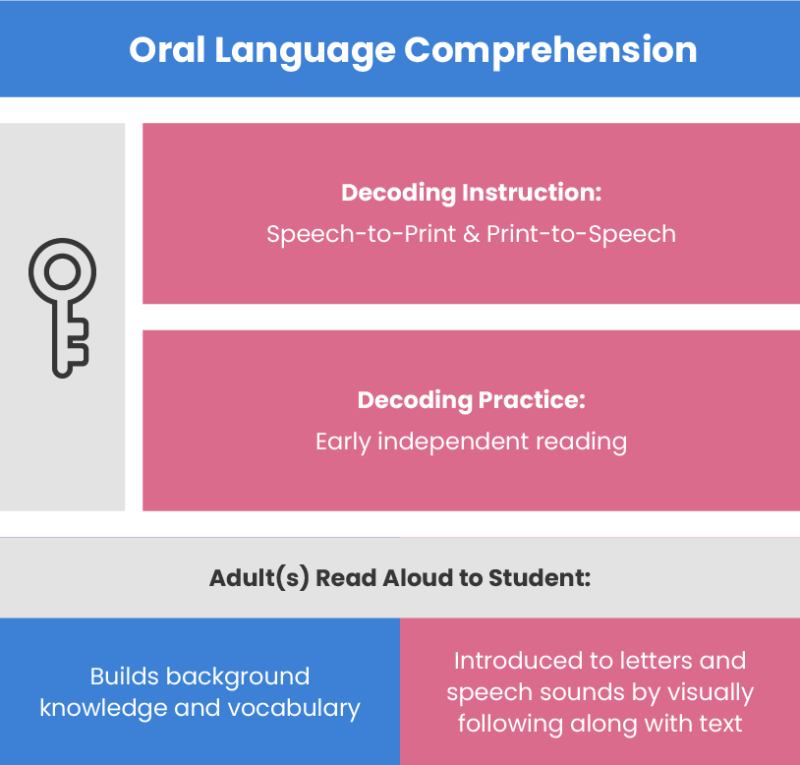

To learn to read a student must be taught to identify printed words, including printed words that they have never heard pronounced before. This is called decoding. Decoding involves pronouncing the speech sounds represented by specific letters and letter combinations and using that knowledge to pronounce printed words. Unlike oral language, decoding requires formal instruction. The pink blocks in these graphics represent decoding, from speech-to-print (spelling words), AND from print-to-speech (reading words).

Here is an example:

From speech-to-print: Listen. Say the word sat. What sound do you hear at the end of the word sat and how do you spell it? (Answer: I hear a “t” sound. I spell it -t-.)

and

From print-to-speech: Look. Here is a written word (sat). What is the last letter in this word and how is it pronounced? (Answer: The last letter is -t-. It is pronounced “t”.)

The key symbol (🔑) on the graphic below signifies that decoding instruction has been shown to be an important key in this virtuous cycle.

But more than just decoding instruction is needed. Books for beginning readers are naturally limited to simple vocabulary and concepts so the virtuous cycle is boosted when adults read aloud to the student. That helps the student build background knowledge and vocabulary through listening (the blue blocks on the graphic). The student’s decoding skills (the pink blocks on the graphic) are also boosted by following the text with their eyes as the adult pronounces words and occasionally talks about how letters represent speech sounds.

As Natalie Wexler (2022) has pointed out, a knowledge-rich curriculum in content subjects is essential for full literacy.

This is the science of reading, a virtuous cycle that results in proficient reading. It serves as a guide to instruction, differentiated for students at various stages in reading development and those with different types of reading disorders.

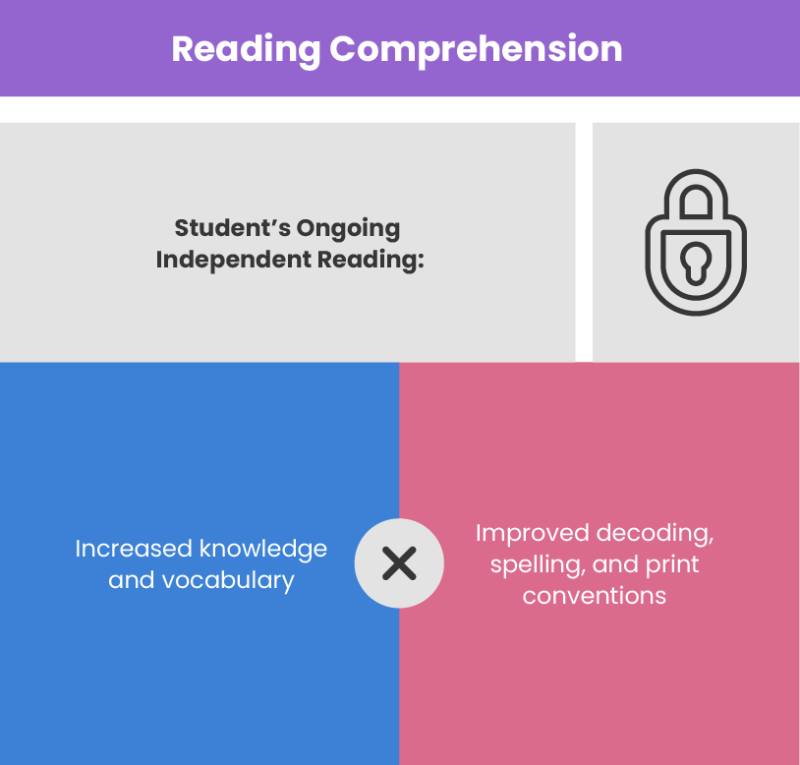

The virtuous cycle moves from early reading instruction (on the right side of the graphic below) to using reading to learn (on the left side of the graphic below). The student who decodes accurately and fluently tends to find reading pleasurable and informative. Because it is relatively effortless and enjoyable, they read more. They read independently. Note the lock. The decoding key is absolutely necessary to unlock the cycle from here on. The more the student reads, the more knowledge and vocabulary they gain. The more they read the better they get at decoding, spelling, and print conventions. Of course, even proficient readers need a knowledge-rich curriculum and instruction in academic subjects.

Click image to enlarge it 🔍

Using the Science of Reading to Help Struggling Readers

The Lexercise Structured Literacy Curriculum™ is built on the Simple View of Reading, with its two components—listening (language) comprehension and decoding (word recognition). Every lesson in the Lexercise curriculum uses a virtuous cycle model, beginning with the student’s oral language, explicitly teaching about sounds and letters, and then word reading and spelling. The curriculum includes conversations about meaningful word parts and vocabulary, and about the meaning of phrases and sentences. Between lessons, there is engaging, individualized practice with immediate feedback.

If you have a struggling reader, writer, or speller, structured literacy therapy might be right for them. You can schedule a free consultation with one of our expert therapists or learn more about our curriculum on our dyslexia therapy page.

Improve Your Child’s Reading

Learn more about Lexercise today.

Schedule a FREE

15-minute consultation

Leave a comment